For a full photo gallery, visit ComeFlytheWorld.com.

Author Q&A

How did this book come to be?

My father worked for Pan American World Airways until I was nine, though I hadn’t thought much about the airline until I saw that its historical foundation would host an event at architect Eero Saarinen’s long-shuttered TWA terminal at JFK airport—which I’d always wanted to see. There, I met two vibrant ex-stewardesses, and eventually others, women in their late seventies who seemed to have lived life elbow-deep in adventure, who spoke of events of geopolitical history as if they'd had martinis with the main actors the night before, who still rarely bought return tickets from anywhere because, as they told me, ‘you never know.’ Those who hadn’t kept flying past the 1970s called themselves former ‘stewardesses’—the outdated name itself pegged them to a job that no longer exists.

I began writing what became Come Fly the World to answer my immediate questions: How did these sophisticated, smart women acquire the attitudes that so impressed me, and why have they been denied credit for their very real contributions to the freedom to roam enjoyed by women of younger generations like me?

Really, though, what was so special about these women?

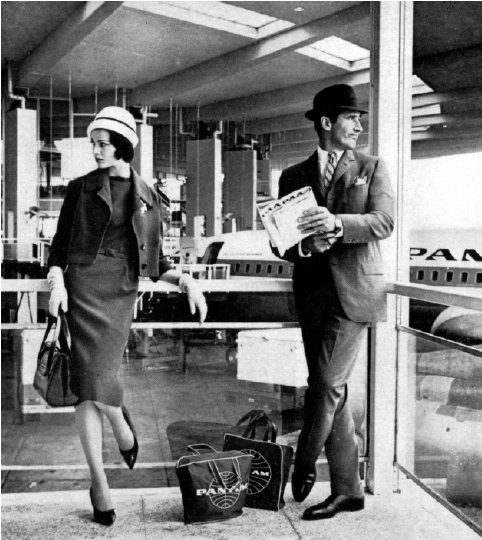

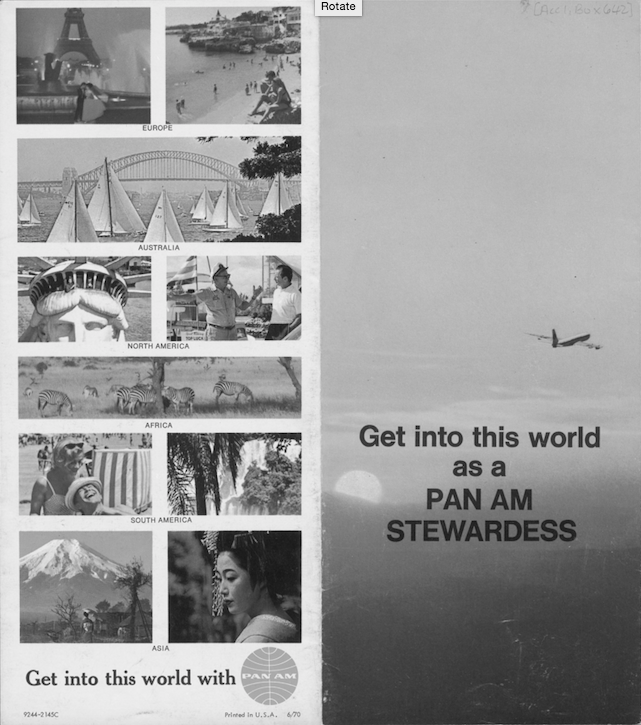

In the 1940s and 1950s, stewardess’ movement around the world un-chaperoned as financially independent, middle-class young women was revolutionary, a true first. No wonder so many women wanted the job! By the early 1960s, American airlines hired only three to five percent of their applicants. Base pay matched other acceptably feminine roles: nurse, teacher, librarian, secretary. For a young woman who didn’t want to totally break ranks with convention, but yearned for a wider world than she’d find in one of those jobs, stewardessing was the thing to do. Perks included insurance, free air travel, paid vacation, and stipends on layovers. And on Pan Am especially, layovers in themselves were extraordinary: multiple nights in an InterContinental Hotel (which Pan Am owned) in Bangkok or Beirut, for example, where Frank Sinatra and Brigitte Bardot also stayed. A job on a plane offered a reason for a woman to travel, and as I interviewed former stewardesses, I learned that the sort of woman who prioritized that impulse in the 1960s is a fascinating person.

What were some of the more splashy and serious adventures and misadventures these women had?

I heard so many stories: a near-drowning off the coast of Liberia and dancing all night in Nairobi, getting tear-gassed in Vietnam War protests and then turning around to take on the role of girl-next-door-therapist-sex-symbol for frightened young soldiers being flown straight into the very war they protested, solo trips to incredible places, and so much more. The total disjunction between the glamorous job and the gritty war charter flights interested me, so my research narrowed down to several women who chose to crew on Vietnam flights.

Throughout the 1960s, planes were fired on while ferrying American troops around Southeast Asia and amid global conflicts like the Biafran War and others, and hijacked to Cuba in the golden era of plane hijacking. One of the main women in Come Fly the World was caught up in a diplomatic kidnapping incident between two newly decolonized countries of West Africa. In the 1970s, another stewardess, a Black woman from Minnesota whose protective mother did not want her even to leave home, traveled to Cold War Moscow, where stewardesses played “shake the K.G.B.” and went to the circus and lined up to buy coveted lipsticks with Soviet women. And many women took charge on multiple refugee flights out of Saigon mere hours before the city was occupied by the North Vietnamese. Amidst all of this and more, the crew parties they threw in various global outposts were the stuff of legend. The job changed many of the women’s worldviews for life; they had all come to appreciate and take ownership of a serious and misunderstood job with high stakes that have never fully recognized in the wider world. The friendships forged amid these times are still strong today.

How did you research your story, apart from interviews with your cast of stewardesses?

A lot of books, from really valuable academic studies to mass-market nonfiction, have been written about the jet age, and those were great help at the start. Though many of them mostly ignore the tens of thousands of women who crewed on the planes, these books offered a fantastic jumping-off point for my interviews with primary sources. My approach was to toggle between reading a lot, interviewing a lot, and then going to newspapers and archives to confirm the details around what my interviewees told me. Once I’d found the women who would be my main subjects, the research was exhilarating. Their memories are all really, really good, by the way, and they were honest when they didn’t remember a certain detail.

Take the diplomatic kidnapping incident in West Africa for example. I found it thrilling to hear about that incident from Tori Werner, in her own words and from her memory, and then find it detailed from different perspectives: in a global history of world events of 1966, in declassified government documents, in corporate Pan Am correspondence, and in the New York Times and Reuters and UPI wire news dispatches. To frame the history first in the personal history and then to show how the rest of the world watched the same event happening made me think a lot about how this electrifying, traumatic period of time in American history has come down to us today.

How did international stewardesses help shape the American feminist movement?

They traveled the world alone or in groups of women, earning their own paychecks, collecting company per diem payments at the concierge desks of hotels: the first large wave of women to work their way around the world. If taking up space is a political issue, all stewardesses of the mid-twentieth century indelibly furthered contemporary women’s abilities to roam.

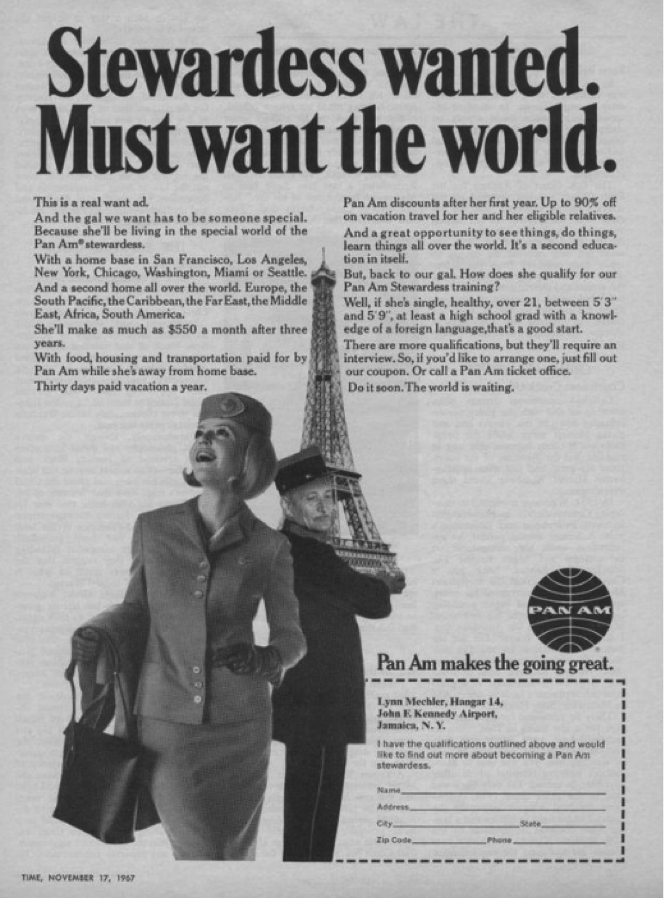

Specific women also contributed more directly, too. In the 1960s, stewardesses were required to be young, unmarried—female by regulation, too—and to meet physical requirements outlined in excruciating detail. (“Attractive appearance will be foremost in importance,” read one airline’s supervisor handbook, and went on to detail the exact physical attributes that made for feminine attractiveness.) Youth and marital status were monitored by rules that allowed for dismissal at a woman’s thirty-second or thirty-fifth birthday, depending on the airline, or upon her marriage. But—for all the reasons above—lots of the women who began to work on airlines in their twenties didn’t want to stop, including after they married. They went to court rather than going quietly. Their love for and dedication to their jobs inspired some of the first legal challenges to unequal employment policies that went on to establish American labor law precedent as it applies to gender.

What did stewardesses think of Coffee, Tea, or Me and all the other sexist books and lewd ads and attitudes toward stewardesses—including from the airlines?

They knew that in reality, Coffee, Tea, or Me was written by a man and bears little, if any, resemblance to the lived experiences of women.

But the far more complicated truth that those ads and books and attitudes reflect is that many stewardesses were both stereotypically beautiful and staunchly independent, feminine and feminist, and mainstream American society didn’t know what to do with women like that in such concentration. Some stewardesses, just like vast numbers of young American women of the era, claimed their own sexual agency both within the context of their work and outside of it. They danced all night in clubs in Hong Kong and Nairobi, they dated more widely than their mothers ever would have, they went out with men around the world. And for some women, the sexism eventually proved to be too much—Karen Walker, in the end, quit the job on a whim when a male passenger dismissively snapped his fingers at her. It was one minor humiliation too many.

Your own love of travel informs this book. Tell us more.

I am most comfortable in movement, and living abroad (for 5 years in Latin America in my mid-twenties) and traveling frequently and easily are huge parts of what make me who I am. It’s shaped both my personal and professional life. As a Pan Am employee’s kid, I traveled with my parents virtually every free moment until, when I was 9, the airline went bankrupt. Employee families traveled standby, and often we wouldn’t know where we were going until we got to the airport. My parents would pack us for hot or cold weather and figure it out on the fly, when we saw which flight had free seats.

My mother credits Pan Am flight attendants with enabling her own travel—they helped her indulge her own wanderlust and travel with two small kids around the world. Standby passes often landed us in first class, where the crew-to-passenger ratio was high, so New York-based 1980s flight crews looked after my sister and me, helped keep us entertained and fed, and made flying into something we always looked forward to. In essence, they gave me the pleasure of travel. I still think best, write best, and enjoy myself most in a window seat, from which I like to post my #windowseatforever vistas to social media.

Why do you think the Pan Am legacy is still so nostalgic for us today?

Pan Am was an airline of historic technical firsts—first air crossing of the Pacific in the 1930s, first mass-market jet flights across the Atlantic in the 1950s, first 747 jumbo jet in 1970—and also of cultural firsts. The Beatles came to the U.S. for the first time on Pan Am, the White House press corps traveled around the world on a chartered Pan Am flight, and when foreign presidents and royalty visited the U.S., they nearly always did so on Pan Am. More than any other American airline, Pan Am made once-distant world capitals and tourist destinations easily accessible to those who could afford it for the first time in history. And as those airplanes beckoned to tourists and businesspeople, the airline was also busy building sophisticated InterContinental hotels in those cities, mountains, and beaches, hiring en vogue architects and designers to create midcentury masterpieces, some of which are still standing today. All of this made for a glamorous aura around the airline. In the stable postwar 1950s, anything international thrilled the general American public—which author Virginia Postrel has written about beautifully—and every angle of the airline, from its airplanes to its flight crews to the cities it invited people to visit and how they would visit them, reinforced that glamour.

But it wasn’t just glamour that creates a sense of nostalgia around the airline. Pan Am flew troops around the world in various global conflicts, and carried soldiers home from harrowing tours of duty. The airline brought a great many refugees and immigrants—from Southeast Asia, the former U.S.S.R., and other regions—for the first time to their new homes in the United States. In my research I heard from a man who said he would never forget the kindness of a blue-suited Pan Am stewardess who found him in his seat as the plane approached New York from the Soviet republic he was leaving as a child, forever, to point out the Statue of Liberty. Many Americans claim such memories; for some veterans, refugees, immigrants, and others with international backgrounds, Pan Am became a powerful symbol of freedom and change.

How do you think stewardess of the Jet Age era redefined the profession as we know it today?

At the start of the Jet Age in 1958, stewardesses were all women, nearly all white, and all subjected to aesthetic regulations and rules about their personal lives. The 1960s-era legal battles that changed those hiring policies had completely shifted the composition of flight crews by the mid-1970s. The court cases opened the job to more men and people of color and dismantled age and marriage regulations for all. And at that point, the tide of people who came in to take advantage of the new opportunities redefined the profession forever.

The job as we know it today is hardly glamorous from the outside—every so often, I see headlines about frustrated flight attendants, who have always been front-line workers, cracking under the pressure. As the women of the 1960s put it in one of the era’s lawsuits, flight crews then were not professional sex objects but first and foremost safety personnel, charged with keeping the passengers of an airplane safe from any of the many things that could go wrong in the air or on the ground, from mechanical failure to hijackings. Back then, stewardesses were expected to uphold glamour, femininity, and sometimes sexual availability in their customer service practices, while also staying attuned to very serious disasters and threats. Today’s flight crews face different tensions—among them the challenge to address a passenger’s every minor experiential complaint in a time of tightening airline budgets—while paying attention to paramount safety issues.

Flying though is still today a flexible job and an incredible way for someone with the same impulses as the women of the Jet Age—“I wanted to see the world,” nearly every single stewardess I’ve ever interviewed has told me—to gain access to a glorious variety of places.